How Liberation Psychology Became My Theology

© 1999 Michele Toomey, PhD

An odd statement for an ex-nun who tearfully proclaimed when she was four: "I'm not Irish, I'm Catholic"! This same little girl at six came home crying from CCD classes preparing for first communion to sobbingly tell her Protestant mother she wasn't going to go to heaven because she wasn't Catholic. This wise mother turned and asked her daughter, "Am I a good mother?" I answered passionately, "Oh, you're the best!" Looking me straight in the eyes she asked, "Then, do you think God would keep me out of heaven?" "Of course not!" I eagerly replied. "All right, then, don't you worry about it!" She gave me a hug and a kiss and I walked away completely relieved.

From that day forward, it would seem, I never believed any tenet, religious or secular, that sounded unfair. My measure in life became fairness, my moral code emerged from fairness, and certainly my spiritual credo reverberated with fairness. My one mistake, however, was that fairness did not begin and end with fairness toward me. Instead of personalizing the credo, I espoused it, I embraced it, and I lived it, philosophically. Mine was the fairness of virtue that thought of others and not one's self. St. Therese of Liseiux was my favorite saint.

Entering the convent at eighteen was a natural outgrowth of such a spiritual commitment to others and dedication to God. I gladly embraced a life of prayer and self-denial to serve others as a bride of Christ, even though it meant leaving behind my six year old brother whom I adored, and loving parents. We missed each other desperately, but that was just part of the sacrifice.

In many ways, after I entered I became a holy non-person, praying, meditating, working, teaching, separated from friends and family except for 2 hours a month on visiting Sunday. I took seriously the admonition to fear "particular friendships" even though for years I didn't understand what it was supposed to mean. I was just "friendly" but not a "particular" friend to anyone. I was prayerful and meditative and considered that spiritual. I was hard working and eager and considered that committed. I was, in effect, living a non-personal life and considered that virtuous.

Then three fateful events changed the course of my life forever, and added me to the equation of fairness. First, and in many ways, most importantly, I became friends with Sister John Paul, and she was definitely personally involved with her life. She expressed herself, not just her beliefs. She taught chemistry and I taught math, and we both played the violin. But the similarities stopped there. She had a dark room, took and developed pictures for the yearbook, for kindergarten graduation and first communion. She had a crystal radio with an earphone that I discovered one day when I walked past her in the corridor after breakfast. As she dust mopped her charge she whispered "The Pope died." Startled I asked her how she knew and she pointed to the cord coming out of her ear behind the starched linens around her face, then to her crystal radio in the shape of a little coke cooler. My spirit skipped and I smiled inside and out, but I walked on. It was silence time.

Sister John Paul was seven years older than I, so she was professed (made her final vows) way ahead of me. I had never really talked to her because it was against the rules to talk to a professed sister if you were unprofessed. This rule of non-communication made me feel strange, as though the community feared we'd be corrupted by the professed. But Sister John Paul was definitely someone I wanted to talk to, and now she had spoken to me.

She also had a license and was one of the few nuns who could drive a car. It wasn't until the community decided to raise money by having a concert, however, that our violins brought us together. She had a music stand and she shared it with me. My life has never been the same. Sister John Paul taught me to expect to enjoy life even though it was hard. She found a reason to give me a ride on a Sunday, which turned out to be a "joy" ride. I had never gone anywhere to speak of since I entered. It was such fun. She even taught me to drive. We did our class preparations on the weekend in her chemistry lab, playing records on a portable record player in silence as we worked and listened to music. Her photography hobby provided her with "petty cash" and she'd buy us cokes and we'd talk for hours. I found a joy in my heart I had given up with my vows. It was my first real "awakening". Time was not only eternal. Time was also now. I began to want to have a life in the present, not just in eternity. It was a fun and happy time.

The second critical event that brought me sharply into focus with time was when I turned thirty. I remembered being eight when my mother turned thirty, and saying to her, "Mom, twenty-nine doesn't sound bad, but thirty sounds awful." Now, it seemed, I had reached "awful". Upon reflection and introspection I found my life and I weren't all I had expected it and myself to be. I felt dulled, uninspired, and stale.

When I entered the convent right out of high school, it was not my original plan. I had intended to go to college first, but that all changed when the novice mistress and the Mother Superior came from Rutland, Vermont to White River Junction to the Howard Johnson's where I was working that summer. They told me God didn't need me to be educated. He just needed me. This was early August and September 8th was the entrance date for the Sisters of St. Joseph. I cried myself to sleep. The next day I called my friend who was also entering, and told her what had happened. She admitted telling them about my decision to go to college first. I prayed and cried and decided to enter in September.

Strange, at thirty, I had received my bachelor's degree only two years before, because I taught school during the year and took courses in the summer. It took me ten years to get my first degree. Ten years of what seemed like 3rd grade math and 4th grade geography at our

Teacher's Training College. Each summer, buses took nuns to summer school where they took courses at St. Michael's College, the College of St. Rose, Catholic University...and each summer I taught summer school and took low level courses at home. Only an occasional night course from a University of Vermont professor who came to Rutland to teach analytic geometry and calculus brought me some brief intellectual excitement. The community never sent me away to college, even when I asked, and they never said why. Somehow, it felt like they were angry at me because they "came and got me" in the first place. If it weren't for the National Science Foundation grants for math and science teachers during the Sputnik era that triggered the fear Russia was getting too far ahead of us, so teachers had better be given more opportunities for advanced study, I would have had no chance to study away at college. The first year I applied, I got 7 grants. My picture was in the local paper. I chose Holy Cross College in Worcester, Massachusetts and loved it.

I had always been labeled as "uppity" by this group of nuns that had invited me to join them and whom I had joined. They said I walked too straight, stood too tall, (I was only 5' 6"), tossed my blond hair when I was a postulant (I had short, bobbed hair covered by a veil), thought I was too smart. Even the letter of recommendation my pastor wrote was considered too glowing. Sister Assumpta, the novice mistress (the same one who came to Howard Johnson's) told me she threw the letter away it was so full of praise.

I not only tolerated this behavior and these hostile attitudes, I never questioned them. Even when the meanness got obvious, I still accepted it. One particular event stands out in my memory, however, as an occasion I should have heeded. My second winter in the novitiate, another young novice and I were sipping cocoa in silence at about 9:15 p.m. (Grand silence began at 9 p.m.) We had just come in from skating around a small rink we had cleared away. It was a moonlit, starry night and we had had a glorious time. In fact, that's how we had lost track of time. Suddenly the silence was broken by Sister Assumpta as she came bellowing down the stairs. She tore into the kitchen and I ran into the confessional ... instinctively seeking sanctuary from this violent and terrorizing outburst. Poor Sister Jean Therese, my skating buddy, stayed and bore the brunt of it that evening. I never understood why she didn't flee. But, next morning came the reckoning. She and I knelt at breakfast in front of Sister Assumpta and asked for a penance. Without a flicker, she quickly pronounced the sentence...no skating for the rest of the winter. This was a harsh punishment. The winter was long and this had been our first skate, and we loved it so very much. It was the winter of my nineteenth year. I was still only a teenager. Yet, we never spoke of it again. Turning thirty brought it back to me. The unfairness of it all was loud in my ears. I wanted something more.

A year passed. My Dad died suddenly at age fifty-five. This was the third critical event in my life. I loved my Dad and he loved me. As troubled as he was, he was an intimate and loving father. His death had a profound effect on me. It forced me again to face myself and time, my use of time. I was thirty-one.

He was gone and I could not have back those thirteen years since I left home and only in the past few years had been allowed occasional visits. He loved Jackie Gleason and the Honeymooners. I never watched TV. When I got home for a visit he'd beg me to stay late enough to see the show, just once, with him. I always declined and obediently was back in the local convent by 7 p.m., as was the rule. Ten minutes away. I longed to be with him but never once did I acquiesce. Never once did I confront the unfairness of such separation from family. I simply obeyed. And now he was dead.

The day he died there was a terrible March snow storm. It took three hours to make the hour trip over the mountain from Rutland, where I taught, to White River Junction. Sister John Paul drove me home. My mother was traumatized. She had thought my Dad was sleeping late, when he was dead in bed. I asked my superior if, under the circumstances, I could sleep at home that night with my Mother and nineteen year old brother. Permission denied. I slept at the local convent, ten minutes away. I was so angry and grief stricken I could hardly bear it. It was an unfairness that finally crossed my line. I would never be the same. Obedience would never again have the hold it had on me. My vows, once unchallenged, came under scrutiny. From that day on, I never again slept at the local conventÊwhen I was home. I never asked. I just stayed at home. Nothing could have stopped me. Perhaps they knew, because no one ever tried. I questioned my commitment to religious life. What kind of charade was I living? How could human grief be treated so callously for nothing but the letter of the law? Legalism under the guise of spirituality? I don't think so. It was a rude awakening.

Pope John XXIII had begun challenging religious communities to confront their traditions, open their windows and let in fresh air, shake the medieval dust off their habits and look at their relevance to today. It was perfect timing for me. I was thrilled and with the same energy I had approached my initial commitment I moved eagerly toward this confrontation of what I knew needed reforming. I wanted to rediscover the essence of our religious life and embrace it, but just as passionately I wanted to reform the arbitrary and the abusive traditions that distracted us from it. I became an outspoken advocate for change. Eventually I was told, "Conform or leave." I did leave, but not before one wonderful opportunity that redirected my life.

It was another year later. I was thirty-two. Sister John Paul, ever the worldly one, saw an article in the paper that said the Ford Foundation was giving fellowships for educational leadership. She thought I should apply. It could provide me with the break I was looking for and she was sure I could easily be seen as an educational leader. Once again, she was opening a door for me. I applied. It would allow me to do whatever I chose to do to enrich myself for one year. Without her I never would have even seen the article.

After numerous trips to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where the selection committee met, I was selected for one of the fellowships. The chair of the committee, a Harvard professor, suggested I attend Harvard as a special student for a year, and take any courses I chose. I had stated I wanted to change fields and learn how to better help my students deal with their life's struggles. Several of my female students had gotten pregnant in recent years (the early 60's), and it had had devastating effects on them. Needless to say, abortion was not a choice, and shame was in abundance. Families uprooted and moved away. The girls suffered. Some married. It all seemed so much more important to their lives than balancing equations or writing proofs. If I were to rejuvenate my soul I wanted to change the focus of my attention. I no longer wanted to teach students a subject, I wanted to teach them about themselves.

So, I went to Harvard in the fall of 1967, in secular dress, as Sister Michele. I had not asked permission to apply for the fellowship and I did not ask permission to accept it. I just did. When I informed the Mother Superior she said I couldn't go. I was needed to teach math in the fall. I replied it was a chance of a lifetime and it would cost the community nothing, and I needed to go. The Ford Foundation even bought me a modest wardrobe, one suit and 3 skirts and sweaters and blouses, and one pair of shoes. I had said I did not want to be at Harvard in a nun's habit. Pope John XXIII's challenge had begun to loosen the hold of traditional garb, anyway, but I was the first in our community to dress in secular clothes with no veil. I ventured out like an astronaut, after fifteen years of convent living, to live in a graduate dorm in Cambridge. It was, by far, the most exciting time of my life.

Scared to death, and thrilled to death, I began my Harvard career. I bought a bike and pedaled my way around Harvard Square. Totally intimidated by my lack of education, I barely spoke in class and just took it all in. I loved everything about it. When the year was coming to an end, I knew I couldn't return to the convent. I hustled around and petitioned the Radcliffe Institute for tuition money. (In those days, Harvard tuition was $3,000.) The Institute offered to give me a grant of $3,000 if the community would match it. I'll never really understand why they agreed, but the community matched the money, and I got myself another year at Harvard. It was truly, the most wonderful time in my life.

That year, Sister John Paul came down to get her Masters in English from Boston College. She was also changing her major from Chemistry to English. We got an apartment in Cambridge, up over a pizza restaurant, and began our life together. It was a fantasy life. We studied, we tried to cook, we went into Boston to the theater, to the symphony, to the restaurants and stores. I applied to become a graduate student in the social psychology department and was accepted. Again I scrounged for money and again I found a way. The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) was paying a full year of tuition and a stipend if a student studied alcoholism. It required a seminar and field work in a local hospital in the detoxification unit. I applied and got the grant. To say I was sitting on top of the world would not be an exaggeration. I felt I'd found my stride. We continued to have a glorious time.

But, there was to be another encounter with destiny. A mole on my shoulder was diagnosed as malignant. I had melanoma. For the next two years, as I received my masters and Ph D from Harvard, I had 4 surgeries and ongoing chemotherapy. It was still the greatest time in my life, but at thirty-five, facing death was not what I had in mind. My life was just beginning. It seemed unreal. So, Sister John Paul (now Sister Helen, since we had taken back our baptism names in this reform process) and I prayed, clenched our teeth, kept silent (unfortunately, we did not know then how to talk through our fear and dread). We just went on with our lives.

We had support from family and loving friends, but hardly a word from the community. Although we never spoke of it, I think it was then we decided that if I lived, we'd never return to the convent. I feel I threw up, off and on, my next two years of school. I wrote my thesis on "The Conflict Theory of Decision Making Applied to Alcoholics." By choosing alcoholism as a topic NIMH funded me for my final year at Harvard. And I did not die. My life had been threatened but it had also been spared. I was shaken, but grateful beyond measure. If ever I learned to "treasure" time it was then. I still treasure every day, maybe not with the same gusto as I did then, but still with an intensity and an urgency for life.

After graduation I accepted a position at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut. Helen and I didn't formally leave the convent, we just left, together.

Once I began teaching social psychology at Trinity, I knew I'd made a mistake. I was doing just what I said I didn't want to do, teaching students courses...courses they cared less about than they did about their personal relationships and problems. Social psychology was better than math because it related to social interactions and processes, but I felt caught. So I decided to teach a course on the psychology of sex roles. It was the newest thing in 1972 and I thought it would be more relevant.

Preparing to teach this course stunned me. When I was at Harvard, Helen and I had participated in the Peace March on Boston Common, picketed the Star Market for Caesar Chavez and the migrant workers, boycotted grapes and lettuce, and gone to civil rights rallies. But I had never looked at sexism. Now I was reading sexist psychology as it had been and as it currently was being put forth, as theory and as fact. I was appalled.

As a former math teacher, I was used to theoretical integrity. How could I be reading that psychologists once taught that women were dumber than men because their brains were smaller? It might not have been as depressing if there hadn't been a current study that reported on a survey of psychologists, psychiatrists and social workers throughout the country. They were asked to list the traits of a healthy male, a healthy female, and a healthy adult. The healthy male was described as strong, independent, aggressive, rational and the like. A healthy female was described as just the opposite, weak, dependent, passive and emotional. To top it off, the traits of a healthy adult were synonymous with those of a healthy male. I was outraged by the unfairness.

In keeping with my lack of personal investment in fairness, I had never considered sexism as something to protest. Now my protestations were overwhelming me. How had opposite sex become synonymous with unequal sex? How had opposite become synonymous with hostility and against?

I not only taught that course, I undertook challenging the biased sexist assumptions underlying it. The seeds of liberation psychology began with this challenge. I set about trying to discover where the integrity of opposites really lay and what was the true nature of opposition within the self.

The fact that psychology let its "science" be used to prove the legitimacy of female inferiority truly angered me. Luckily, that study had alerted everyone, and gender-bias became a legitimate topic of research in psychology in the early 70's. Not a status topic, not easily earning tenure for its authors, but a concern to be explored by those psychologists who were drawn to it.

At first I joined them with pride. My only paper at a national APA (American Psychological Association) conference was in 1973 as part of a panel from Division 35 (The Women's Division). I spoke with excitement on sex bias. Not particularly with enlightenment, but definitely with excitement. It was well received. I felt launched in my new profession. But college teaching did not excite me. Challenging sexist psychology did. In 1976 I founded Women's Workshop and devoted all my energy to confronting the errors of psychological sexism. I offered workshops, lectured, researched and thought.

I pursued the question of opposites and found myself feeling energized and gaining insight, but my Workshop participants weren't keeping up. I thought all I had to do was expose them to the error of seeing opposite as unequal: strong-weak, independent-dependent, aggressive-passive, rational-emotional, male-female, superior-inferior. To my amazement and dismay, they had an internal belief system defining who they were and how they were to relate to themselves and others that went along with genderized opposites. Good and evil, right and wrong were the judgments that were paired with the traditional approach to opposites.

They were good if they were gender appropriate. Males were as caught as females, but at least their gender box had status. The messages were imprinted on their psyche in childhood and changing them was no small task. Not what I had expected.

Just telling them it was a myth didn't free them. It only frustrated them. So I was forced to do individual sessions with them to try to discover what it would take to free them from the oppression of their own sexist, judgmental world view. So, for twenty-three years, I have listened to and researched the primary sources, the women and men who come to the Workshop seeking to be free of their own oppression. I called my orientation Liberation Psychology.

What I discovered is an awesome testament to the integrity of our nature. I feel I found the path through the labyrinth of the psyche, to the soul. By choosing to begin with the basic assumption that opposite did not mean hostile or unequal but rather that it meant only opposite, I began with four basic assumptions:

- The self is born with integrity, whole and at one.

- The self is by nature paradoxical.

- Each of the self's paradoxical forces, capacities or dimensions are equally legitimate.

- These paradoxical forces are governed by integrity (honesty) and they are meant to be reconciled with each other in order to maintain the self's integrity (wholeness).

With these assumptions, the superiority of conquest was removed completely from the traditional orientation. These assumptions fly in the face of opposites being at war, conquering each other, and that the self's main arena is a battlefield where gender appropriate traits win out over inappropriate ones and good conquers evil. We are taught to aspire to conquer disease, conquer space, and conquer our demons. I began the pacifist's search for liberation and for truth. I looked for the divine in integrity, in fairness and respect, in intimacy and care. I looked to find a oneness with human nature and nature's nature and a way to live in accord with nature not at war with it.

The tyrannically mean voices that my students used against themselves to judge themselves inadequate, wrong, inferior, crazy, stupid...did not lend themselves to eradication. I tried everything. Finally, I realized these forces must be converted not eliminated. The integrity of my system was being preserved by the integrity of my search. It was against its initial assumptions to "eliminate" anything. So I sought to understand how to convert the oppressive messages that had been imprinted on their psyches from childhood.

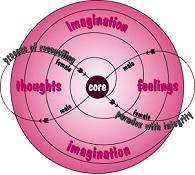

My image of the inner world emerged as a spiral with an infinity sign superimposed on it horizontally. The spiral represented the continual movement within, connecting the past, the present and the anticipated future, connecting body to soul and soul to body, mind to heart and heart to mind, conscious to unconscious and unconscious to conscious, self to self, self to others and others to self. I saw the imagination as the translator for these various entities to communicate with each other, so metaphor and imagery became very important in my work. I had been shown that cognitive awareness was not enough. Intuitive insight and metaphorical connections were essential.

The infinity sign represented the pathway for processing the thoughts, feelings and imaginings that got triggered continuously in our communication network. The interaction of it felt like our core, our essence, our soul because it was the central interconnectedness of our being. Thoughts and feelings were moved through the infinity sign communicating with each other through the imagination but everything met at the core. At least, it should meet at the core, if the integrity of the process was maintained as we participate in it.

I discovered that some of us are born with the sequence of "thoughts to feelings" and some of us are born with "feelings to thoughts", much as we are born right or left handed. The stereotype would have it that gender determines the sequence: males are thoughts to feelings and females are feeling to thoughts. I found no truth in that sexist assumption, but even if it were true, it would not indicate inferiority or superiority, only difference. If we are born with the sequence of thoughts to feelings, I chose to describe that as having "informed feelings". If we are feelings to thoughts, I describe that as "felt thoughts". Either way, the infinity sign intersects and thoughts and feelings meet and felt thoughts or informed feelings come together as one.

Each perspective has its unique advantages and disadvantages, and each needs to include both feelings and thoughts. It would seem many artists, musical and theatrical or visual, have the sequence of feelings to thoughts, and many scientists and theorists have thoughts to feelings. The great ones maximize both dimensions and work from their core where they meet, as well as from their unique orientation. Neither is preferred. Each is to be valued. Neither should be limited to only one - - thoughts with no feelings or feelings with no thoughts.

There was still something missing in my approach, however. I was still left with the abuse of power so oppressing my students. They beat themselves for doing things wrong or they beat on others (figuratively or verbally, of course). They were often anxious or depressed, alienated or unhappy. They were victimized by themselves and by what they tolerated from others, so they were not free.

Then seemingly out of nowhere, it came to me. Define power as energy, instead of as control, and I could reclaim power. I was overcome with excitement. Of course, envision power as energy, as force, then movement became the exercising of power, and strength can be measured in terms of intensity! It was for me a light bulb moment on the magnitude of Thomas Edison. One momentous AHA! Movement, both of body and of mind and spirit was the exercising of power, and stuckness, either in mind or body was a loss of power.

The ramifications were mindboggling. Without defining power as control and strength as the ability to conquer or control, power was no longer a male dominated force. Men were no longer stronger than women or more powerful than women. I had equalized power and taken the essential basis for genderized polarity out of contention. The system was becoming whole, as it was meant to be, if it was true to the integrity of our nature.

Now, I needed to consider the source of our energy. If the need to control or be controlled is not the source, and if conquering evil is not the motivation, then what could it be? I realized it was desire. Desire is the source of our energy, of our power. The more intense our desire, the more energy we generate. That made such sense and made depression, with its lack of desire and little energy so understandable. Movement seems to slow to a crawl in the depressed and they often respond well to walking if they can get themselves to walk, since it brings bodily movement. Anxiety, with its unleashed pain and fear that desires safety but has no clue where to find it, generates chaotic and frenetic energy in its frantic search to satisfy its desire to be safe. To see desire as the source of our energy gave us a limitless supply, which of course, is bounded only by the limits of the body. Thus, again we encounter the need for reconciling our paradoxical capacities to find the integrity of our boundaries.

Inadvertently, however, I found myself bumping into Catholicism, or perhaps more accurately, crashing into it. In Catholicism, desire is traditionally seen as a source of temptation and morality sets imposed boundaries, for our protection. The virtue of religious life is the self-denial and very strict boundaries. The ideal is living without desire, except to be god-like and at one with God serving others. To give desire a central, legitimate place as the wonderful driving force of our being is to confront the Church's teachings on good and evil. I had already skirted around the confrontation with original sin and morality by claiming that the self was born with integrity and its natural integrity governed its inner communications system. Now I was giving desire a place of honor, not to be feared, controlled, ignored or eliminated, but to be respectfully listened to as a driving force of energy. To challenge original sin, morality, and desire was somewhat intimidating, but I knew it was what the integrity of the system required.

I needed to consider that this force was harnessed by integrity, not by fear or imposed morality, and that integrity provided the governing principles. As I listened to my students, I knew their themes were universally the same. They struggled to find intimacy, oneness, with themselves and others, and to protect and be protected from themselves and others. I realized that the fundamental paradoxical desires for the self are the need for intimacy and the need for protection. There was a natural sequence here, the need for intimacy must precede the need for protection, or we cannot have intimacy since intimacy needed vulnerability and openness while protection needed watchfulness and guardedness. It was a small step from there to conclude that the integrity of the process to reconcile these two paradoxical desires/needs provided the boundaries for self-indulgence and abstinence. The natural integrity of the system would alert us to the boundaries and when we were violating them or allowing others to violate them and therefore, violate us. The only evil in this system is violation of our boundaries. Our involvement in this process of finding and establishing our boundaries requires that we preserve the system's integrity by being accountable to it and to ourselves and each other. Confrontation with accountability is the vehicle that keeps the integrity, ours and the system's, intact when we participate in it. It determines the limits and boundaries as we reconcile our paradoxical desires. The integrity of the system was intact. Liberation psychology encompassed the integrity of it in its entirety. Another giant AHA! A totally fair system.

Catholicism had been challenged full flank. Original sin was out, because I proposed that we are born with integrity, whole and at one. The evilness of our desires was out, and therefore, being at war with ourselves was out, because I proposed that desire was the source of our energy, and that every force, every desire was equally legitimate. Intimacy not conquest was the goal, and intimacy was achieved by reconciling our paradoxical desires, not conquering them. Morality as an imposed right and wrong on our system was also out. Integrity was in, replacing morality, and integrity is known from within. So we must listen to ourselves, not fear ourselves. Integrity is not culturally, societally or religiously determined. It is human nature determined. Some things are essential truths and are not relative. To my mind, that is true of the nature of the integrity of the self with its complex communication system governed by this integrity.

My mother, who converted to Catholicism after I entered the convent, cried when she first read my original writings, telling me I couldn't really believe what I had written. Strange how things come round and yet don't meet. I tried to tell my mother she started it all, but she would have none of it. As time went on, she got used to my ideas and saw that my heresy didn't appear harmful.

As for intimacy with God, it became clear that God was within, and that intimacy with our core, our essence, our soul, was, indeed, oneness with God. This was not foreign to Catholicism, so that was interesting. However, that did not leave room for God to have gender. God, as the essential oneness is a spiritual force not a He or a She. God is "It". As long as God is "He" there will always be sexism, and in my opinion, error. Oneness with the cosmos, and with ourselves, is the awesome fulfillment of the human need to be intimate and at one. Spiritual oneness is our fundamental human right-need.

Liberation psychology had evolved into a total belief system emanating from a nature myth that had living in accord with nature at its core. Liberation became the freedom to choose intimacy. The integrity of reconciling paradoxical forces became the governing principle for the choice. Accountability to this integrity becomes the vehicle for participation in this process without violating it. Desire became the essential force. The spirituality of the inner world had the presence of the divine as its ultimate intimate connection, at its core. There were no toxic fumes, no wars, and no casualties. Liberation psychology is a pacifist's dream, and an ecological utopia, providing the potential for an awesome existence of integrity, intimacy and well-being.

Liberation psychology had become my philosophy, my psychology, and my theology. It feels very presumptuous of me to claim this, and in many ways I haven't had the stature to match my work. Perhaps that's my good convent training. Perhaps it's my own sexism, as a woman, not daring to claim something so monumental. However, it is time, in fact, long overdue. I am ready not only to claim it, but to proclaim it. |